|

Journey to Myanmar - Crossing the Rubicon Mixed Feelings I was on a Thai Airways flight from Bangkok to Yangon (Rangoon). It was going to be a short flight- just 75 minutes - but I felt that I was crossing a psychological barrier much greater than the short and convenient flight might suggest. Myanmar (Burma) was the last country on the Indo-Chinese peninsula that I was touring. Since 1997, using Bangkok as my gateway to other destinations in the region, I had visited Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos. And, like many, I had felt uneasy about going to Myanmar, partly because of the pariah status of the government, with its reputation acquired over many years for widespread human rights violations, and partly because there seemed to be scant information about this rather isolated country. When friends and acquaintances heard that I was going to Myanmar, they would react by saying, “Is it safe to go there?” or “Is it hard to get a visa? “ But everyone that I met who had been there marveled at the beauty and rich cultural and architectural heritage of the country and I could no longer contain my curiosity and yearning to see it. My tourist visa took one week to obtain at the Myanmar Consulate in New York, and I was given 30 days - although I only had time for a 6-day visit. While I was still musing over this inner conflict, the stewardesses started serving drinks followed by an elaborate breakfast. Soon afterwards, immigration and customs declaration forms were handed out and I slightly chafed at the fact that I had to declare any items of jewelry, video cameras and foreign currency above a certain amount. It reminded me of what it used to be like entering and leaving China about 10 years ago, but China has done away with all that. And I have been spoiled by the ease and speed with which one goes through customs and immigration in Bangkok. Yangon I had barely finished filling out the detailed customs form when the plane touched down and we were in Myanmar! The airport terminal was an attractive, open sort of building in traditional Burmese style, which offset the slight feeling of foreboding that I had about entering a highly-regimented country. When I reached the immigration officer’s counter, I could already catch a glimpse of the lobby area where luggage is collected and there seemed to be a number of guides waiting for arriving visitors. The men and women were all immaculate in white shirts and longyis (sarong like wrap-around skirt usually made of cotton and dyed in beautiful colors and designs). This was the first sign of how the traditional way of life has endured in Myanmar. Immigration seemed routine and straightforward but at customs I had to declare specific amounts of currency I was carrying and was obliged also to change 300USD into their Myanmar equivalent which are Foreign Exchange Certificates (or F.E.C.s) denominated in dollars and for internal use within the country only. This form of currency was in use in China some 10 years ago but has been abolished there. After completing the procedures, I was greeted warmly by a tall, statuesque woman with waist-length black hair, and a small, slight young man, both in traditional Burmese attire. I was whisked into a chauffeur-driven car which drove along a tree-lined highway from the airport into the center of Yangon. I was struck by how green and relatively unpolluted Yangon was compared with Bangkok. The tour guide, Myint Myint Oo, (who preferred to be called just Myint) explained briefly to me the tour itinerary, which was handed to me, neatly typed out, along with maps of Yangon and Myanmar. Mr. Ko Ko Latt, one of the managers of the tour company with whom I had exchanged numerous faxes before my arrival, was a bright-eyed man in his 20's with a cheerful mien and a ready smile. “Please join me for dinner tonight, Mr. Tao.” My long-awaited tour had begun, and I felt in good hands. Faded Elegance of a Great Metropolis The car pulled up at the Kandawgyi Palace Hotel, there was a flurry of activity, with bell-boys rushing to take my luggage and doormen ushering me into a beautiful lobby decorated in the Burmese style with polished teak furniture and pots brimming with flowers everywhere. The front desk staff immediately asked me to relax in the lobby while Myint helped with registration formalities. A cold towel and a refreshing glass of iced Shan tea (Shan is a state in the north-east the size of Bangladesh) were brought to me on a tray, while I sat in comfort on one of the sofas, richly-upholstered in silk. This was Asian traditional service at its best, I felt. A member of the staff, petite and fetching in a jade-green bodice, led me toward my room along a corridor open on one side. Before reaching it, she pointed to a gold pagoda glittering in the sunlight, erect and imposing, in the distance. “Shwedagon Pagoda, Sir,” she said proudly. When we reached my room, and the bellboy threw open the door, I gasped at the view through the window of a crystal lake thick with lilies, at which point she said, “And that is the Kandawgyi Lake, the Royal Lake of Yangon. Enjoy your stay, Sir.” I had no doubt that I was going to.

Lily-covered Kandawgyi Lake, Yangon Our first destination was the Sule Pagoda, which is a structure believed to be over 2000 years old, an island of calm and meditation in the busiest part of the capital, where several main thoroughfares intersect. Two missionary monks came from India carrying with them a hair relic of Buddha. They were given permission by the Mon King of Thaton in Southeast Burma to build a pagoda on the site of the present Sule Pagoda. At the entrance of the Pagoda, there were many vendors selling flowers for worship, and other religious paraphernalia. It is interesting how the pagoda is also part of a building housing, on the side facing the street, rows of tiny shops selling mostly watches, film and camera accessories. Near the pagoda are a number of guesthouses for monks and schools for Buddhist learning and discussion. In the vicinity of

the pagoda are three structures that, to me, symbolize the 3 eras of

Myanmar’s evolution. There is

the High Court, a Victorian building in red and white built during the height

of British power, representing complete colonial control and domination.

Then there is the City Hall, inaugurated in the 1960's as a venue for

important gatherings and events, which was originally a British building on

which Burmese architectural features have been grafted, creating a pleasing

overall effect. The successful

melding of the Colonial and Burmese styles epitomizes the acceptance of some

continued British influence in Burmese life, and finally the Independence

Monument, a simple, vertical monument in a nearby park (named after a Burmese

war hero who fought against the British in the early 19th Century)

can be said to be the symbol of a modern, assertive Myanmar, completely free

of the shackles of colonialism. Myint also pointed out a blue-and-white Indian mosque,

which she said was built for the Indian laborers who were brought over by the

British during the colonial period. There

is certainly a variety of architectural styles here in the commercial heart of

Yangon, but a number of fine colonial buildings have survived intact, like

aristocrats past their prime who continue to carry themselves with dignity and

a kind of faded elegance - the Post Office, the Telephone and Telegraph Office

and the Myanmar Travels and Tours office (the government tourist office) to

name but a few. The Harbor and Botataung Pagoda

Further along the waterfront stands the Botataung Pagoda. The word “Botataung” means 1000 military officers. Based on the same story as the one relating to the Sule Pagoda, hairs of the Buddha were escorted by 1000 military officers from India to the banks of the Yangon River 2000 years ago and enshrined in the original building of the pagoda. Allied bombing during the Second World War destroyed it, and the rebuilt pagoda is lined with glass mosaic inside and has many glass cases displaying various relics. At the entrance I noticed a young girl sitting behind her wares, in this case a huge vat of fresh yogurt, which must come as welcome refreshment for many after visiting the pagoda. My guide Myint at harbor The

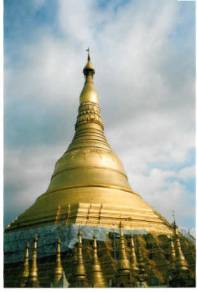

Shwedagon “It towered, aloof, impressive

and mysterious against the night.” This was W. Somerset Maugham’s evocation of the Shwedagon in 1930. According to Burmese legend, the Shwedagon dates back to the coming of the five buddhas who would guide the next world towards Nirvana. But in 260 B.C., the Indian Emperor Ashoka, purveyor of Theravada Buddhism, came to pay homage to the pagoda, and ordered it to be restored, starting a tradition of successive kings enlarging, embellishing and maintaining it. Extensive alterations were carried out in the 15th Century when one of the Burmese queens had the stupa raised and gilded for the first time.

It is not easy for non-Burmese to fully appreciate the reverence and affection with which this most sacred and eminent of pagodas in Yangon is held by the people of Myanmar, but, for me, seeing it struck a resonant and powerful chord. We entered by the southern entrance, and emerged from a lift built in 1996 in celebration of Visit Myanmar Year, to find the Shwedagon in full view. It was already late afternoon, but the golden pagoda glittered under the only slightly waning sunlight. It was silhouetted against a tropical azure sky with white clouds hanging low in the distance. I gasped at its timeless beauty and solemnity. What emanated from this structure was an aura of solidity and permanence that transcended wars and crises and human greed and ambitions. The lower stupa represents the Buddha’s inverted begging bowl, and the slender upper stupa tapers to end in an elegant “hti” or umbrella, from which hang bells and priceless jewels. The entire structure is gold and throughout the centuries, kings and queens have been unstinting in re-gilding it or adding to the fabulous treasures of its jewels. I was struck by how the fact of the pagoda being a precious structure of astronomical monetary value did not take away from its spiritual power - a quiet but awesome power.

One can take the Shwedagon on the level of a religious icon calling forth the deepest, purest and most devout feelings of true believers. It was Sunday afternoon, and all around me were groups of worshipers, who would kneel, put their palms together and pray - with an almost child-like reverence and fervor. The intensity of their feelings swirled around them until it

touched me as well. Never in my life had I experienced anything quite as moving. And all of it was done with infinite grace and smoothness. There was never a jarring moment, rough word or inappropriate gesture. They would move to a sacred spot or in front of a shrine or statue, pray, and then swiftly and almost imperceptibly move on somewhere else when they had finished. The lay worshipers were dressed in brilliantly colored longyis and elegant traditional attire, while the monks wore robes of maroon color and the nuns robes of a delicate salmon pink. At the same time, worship here and elsewhere in Myanmar is also a social activity - whole families were here today, including young children. In between periods of intense and concentrated praying, there was a relaxed atmosphere of conviviality, an almost carnival-like feeling. One could see that the Burmese are an enormously gregarious people. In fact, pilgrims would often come in groups, spend the whole day here and bring their lunches which they would eat sitting cross-legged on the immaculate marble floor of the pagoda platform. Although the pagoda itself is the main attraction, there are rows of shrine halls with small stupas ringing the main pagoda and other shrines along the outer edge of the platform. Situated at the southeastern corner is a sacred banyan tree, ancient and proud, with thick intertwining branches clustered at its base and spreading its leafy shade over a wide expanse. At the eight cardinal points on the base of the pagoda are the planetary posts, where pilgrims worship. In Burmese astrology, the week has eight days, with Wednesday split into morning and evening, and each day is represented by both a planet and an animal. So those born on a Thursday would go to the Jupiter planetary post, light a candle, offer flowers and pour water over the image of the rat, which is the animal for the Thursday-born. Khin Myo Chit, in her delightful book “A Wonderland of Burmese Legends,” describes the Shwedagon in the following way, “The majestic Shwedagon Pagoda (that) is never apart from the land and people - in joy or in sorrow, in prosperity or in poverty.” Is it any wonder then that, in August 1988, a time of great national ferment and yearning for democracy, Aung San Suu Kyi assumed leadership over the popular upheaval by giving a major speech right here at the Shwedagon, captivating the huge crowd with her eloquence, charisma, and passion? That was the opening salvo of her struggle for the hearts and minds of her people, an intensive political campaign that led to a landslide election victory in 1990 for her and the National League for Democracy. From that day onwards, Aung San Suu Kyi and the Shwedagon would forever be inextricably linked in the annals of Myanmar history. Dinner

in the “Karaweik” The

young manager of the tour company, Mr. Ko Ko Latt, was host at the dinner in

my honor at the restaurant in the interior of a stone barge (a copy of a royal

barge, I am told) moored on the eastern shore of Kandawgyi (Royal) Lake, just

minutes away from my hotel. The

barge is in the shape of a “Karaweik” or “Hinta”, a mythical bird of

Burmese legend, and was built by the government in the early 60's

in order to put its citizens in closer touch with their country’s

cultural heritage. From a

distance, silhouetted against the indigo sky, festooned with lights that cast

their beams on the smooth surface of the lake, the barge had a slightly

bizarre but indefinable appeal. Before

dinner, Myint led me around the “deck”, and it was delightful to feel the

coolness of the evening breeze after the relentless heat of the day.

She spoke evocatively about the boat races that take place every year

on the lake in December, the pageantry and festivity of which I could almost

visualize there and then. In the

stillness of the night, we could hear the musicians tuning their instruments

and preparing for their performance this evening. One of the young dancers was already in full classical dress

and smiled winsomely at us when we passed.

It was an enchanting moment. What

followed was an evening of fine food, gracious hospitality and the best in

traditional Burmese music and dance. Mandalay It is interesting to note that Mandalay is one of only two or three major places of interest in Myanmar whose names have not been changed by the government - and that is fortunate. In his novel, “The Gentleman in the Parlour,” Somerset Maugham said it well,” Mandalay has its name; the falling cadence of the lovely word has gathered about itself the chiaroscuro of romance.” But of course it is much more than just a name. It is the second largest city in Myanmar, with a population of one million. It is considered by the Burmese to be a center of traditional arts and crafts, music and puppetry, and the repository of the old, time-honored ways, untainted by either the colonial legacy or modern cosmopolitan influence the way Yangon is. (One might say that Mandalay stands in its relationship to Yangon much as Kyoto does to Tokyo, or Jogjakarta to Jakarta.) Mandalay is a place where courtly manners and affection for the monarchy have endured. In the middle of the 19th Century, when the British already occupied and controlled Lower Burma, King Mindon, now limited to Upper Burma, wanted to reassert his sovereignty and prestige by building a new capital and palace in Mandalay, though he cited religion as the reason for it.

Strolling out of Mandalay airport, I was struck by how refreshingly cool it

was after the sultry heat of Yangon. And

all around us were brilliant pink and white flowers in full bloom - it had the

aspect of a garden city. Once

again I was whisked into a car by a courteous driver while the porter dealt

with my suitcase, carrying it on his shoulders, straining under its load, with

his brown and sinewy arms showing under their short sleeves.

For a moment I felt a twinge of unease, as if I was a successor to the

colonial overlords of the past. After

checking in at the pleasant though modest Swan Hotel, we sped off to Mandalay

Palace, almost completely destroyed by allied bombing during the War save for

its walls. The Japanese military

was entrenched in the Palace along with arms and ammunition, and Allied

commanders claimed that there was no other way of dislodging the enemy.

But as if to leave no doubt as to who is in charge now, the Myanmar

Army itself is encamped in the palace grounds, lending a slightly forbidding

air to the place.

Mandalay Palace’s spires and original walls The original walls are all that remain intact of the palace. They are brick walls of a dark red that look very imposing as one drives parallel to the palace. There are a total of 12 white gates, 3 on each side, and on top of each gate is an elaborate, tapering, wooden spire known as a pyathat, which Somerset Maugham rather quaintly describes as a “belvedere” in his book. If one were standing outside the eastern wall of the palace looking north on a clear day, one would get an unobstructed view of Mandalay Hill, studded with pagodas and temples. The palace is surrounded by a moat on all sides, and seems to dominate the center of Mandalay. Here is Maugham’s powerful evocation of the palace wall:

Shwenandaw Monastery This monastery was originally part of Mandalay Palace, but in 1879, King Mindon’s son Thebaw (the last king of Burma) had it moved out of the Palace grounds to a site near the foot of Mandalay Hill because his father had died in the building. This turned out to be an extraordinary bit of luck for Mandalay and the Burmese people, since it was spared the fate that befell all the other buildings in the Palace of being reduced to a pile of ashes and cinder during the Second World War. Paradoxically, what was considered to be its inauspicious nature led to its survival intact as a national monument of great distinction and beauty.

Picture at left: Shwenandaw Monastery’s finely-carved doors and lintel Mahamuni

Pagoda The words “Maha Muni “ mean “holy image” and the figure of the Buddha housed in this pagoda, originally built by King Bodawpaya in 1784, is one of the holiest in Myanmar, perhaps second only to the Shwedagon in Yangon in the degree to which it is revered by the people. There are differing accounts about how the image, originally in Rakhine or Arakan State in western Myanmar, came to be here. The Myanmar government’s web-site simply states that King Bodawpaya got his son to bring the image over to Mandalay. In her guidebook on Burma, Caroline Courtauld writes,” According to an inscription in the pagoda, Bodawpaya coaxed his Buddha image to Mandalay by the ‘charm of piety.’” But the information provided to visitors in the pagoda tells a complex and intriguing story, putting the Buddha image at the nexus of the region’s bloody strife and conflicts: One of the Burmese kings had to enlist the assistance of the King of Arakan in fierce wars against the Siamese, and after a joint victory against the latter, as a reward to the Arakanese he had to give them the Maha Muni (which implies that it was originally in the possession of the Burmese King). The Burmese had been trying to get it back from the Arakanese ever since, and eventually in 1784 Bodawpaya invaded Arakan and recovered the image along with a set of Khmer bronze statues which is said to have been part of the war spoils of the Arakanese in their military campaigns against the Siamese, who in turn had looted the statues from the Khmers in a previous invasion of the Khmer capital of Angkor.in 1431. The bronze statues, some in fragments, are also on exhibit in the grounds of the pagoda, and Myint spoke poignantly of how pilgrims who come to worship here tell stories of the statues taking human form at night and shouting plaintively, “Back to Arakan! Back to Arakan!” In front of the seated, twelve-and-half-feet-high bronze image decorated with layers of gold leaf were throngs of pilgrims. There is a hierarchy at work here. The most sacred front part closest to the image is accessible to men only. The next section is reserved for the wives and families of VIPs and local dignitaries. And then the third section behind is open to everyone. An atmosphere of serene but intense worship pervades the pagoda, which is an elegant building with long colonnades and imposing archways and pillars. Saffron-robed monks would be engaged in prayer along with lay worshipers and there was an old woman dressed in upcountry Shan clothes making a donation at one of the alms-boxes. Mandalay is a great center for pilgrimages by the devout among the Shan and Kachin, partly because of its convenient geographical location in Upper Myanmar. The

Mandalay Marionettes Myint presented me with an excruciating choice that night. She said I could either view the moat and the palace at night or see a puppet show. Having read Maugham’s description of the palace bathed in moonlight, I really wanted to see that for myself. On the other hand, a classical puppet show was a cultural experience I was very loathes missing. In the end I opted for the latter, but only after much hesitation and soul-searching. So after dinner I was brought to

the Garden Villa Theater, whose location was tantalizingly close to the moat

and the palace, in fact. According

to information given out by the theater, puppetry in Myanmar dates back

several centuries, but had its origins in her neighbors - China and India.

By the eleventh century, puppetry in this country was already well

established, and historical records show that the ancient art was not only

practiced in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries but enjoyed enormous

popularity at the royal court. But along with the fall of the Burmese monarchy, puppetry

experienced a precipitous and near-irreversible decline.

The Mandalay Marionettes are a team of local master-puppeteers who had

been discovered after a great deal of effort.

The Burmese are immensely proud to have been able to achieve this

revival of a revered and thoroughly authentic art combining the artistic

traditions of drama, music and dance as well as wood carving, sequin

embroidery and painting. Indeed,

the puppets themselves, exquisitely made, seemed infinite in their variety,

and were displayed on the wall of the theater to be viewed by the audience at

their leisure.

All in all, it was a culturally memorable evening that I was unlikely to forget easily. The Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) “No other river of comparable length in the whole Southeast Asian region has the distinction of having its source and course entirely inside the same country. Thus, the River Ayeyarwady is ours - our very own.” This is a quotation from the tourism section of the Myanmar government’s home page on the Internet. There is no doubt that the Burmese have an unusually strong sense of proprietorship about their great river and a deep and abiding emotional attachment to it. And it is touching to hear them talk about it with a mixture of pride and love. A very short stretch of that other mighty river in Southeast Asia, the Mekong, (which flows through six countries), fringes part of remote Shan state in eastern Myanmar, marking the border between the latter and Laos. Although the Mekong has been a powerful force binding the neighbors on its shores closer and closer together, in both a practical and psychological sense, its impact on Myanmar has been less significant, for geographical, and probably also political reasons. By contrast, the Ayeyarwady has its source in the Himalayan mountains, runs its majestic course from Kachin state in the north, through the historic and cultural heartland of the country, Sagaing, Mandalay and Bagan, into southern Myanmar, and eventually becoming the myriad of waterways of the vast, flat, and extraordinarily fertile alluvial delta that made this country a leading rice producer, before merging at its mouth with the Andaman Sea. It is not only the economic lifeline of Myanmar, but also the stuff of legend and song, the wellspring of joy and sorrow. The Burmese cannot imagine life without their beloved Ayeyarwady. It was with this in mind, and with a mixture of curiosity and reverence, that I started my long-awaited Ayeyarwady cruise - it had the makings of a pilgrimage. It was six o’clock in the morning in Mandalay.

I was sitting, still drowsy, in the cabin of the Golden Hinta, one of

the public river ferries plying the route between Mandalay and Bagan.

Too excited to eat the breakfast so neatly packed by the staff of the

Swan Hotel, I nibbled at the ham sandwich.

Soon, the boat pulled away from Mandalay pier and we started the

day-long journey to Bagan on the fabled Ayeyarwady.

But before long the mist had all but dissipated, and we were well on our way. As the river widened, we passed under an impressive steel bridge spanning the two banks, until recently the longest in Myanmar. All manner of river-craft could be seen - tiny boats with lone fishermen casting their nets, flat-bottomed boats with wide berths transporting agricultural produce, and, of course, the heavily-laden barges carrying the huge teak logs from upcountry down to the major centers of the south. Now and again, we would be startled by the breathtaking beauty of the green shores carpeted by brilliant yellow flowers. The

passengers started to relax and settle into the 10-hour journey.

Down in the cabin, French tourists buried themselves in guide books

about Bagan. A couple of

Singaporeans, railway men by profession, were asking searching questions of a

Burmese man about railways in Myanmar. A

group of Germans made themselves comfortable in deck chairs on the stern,

while Burmese upcountry passengers were quite contented with sitting on the

I soon discovered that the ferry boat was manufactured in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, southwest China, not far from Myanmar. This fact is eloquent testimony to the active trade that goes on between the two countries, which seem to enjoy fairly amicable diplomatic relations also. We made two stops along the way at small villages. At the first one, women from the village came in their finery to sell large slices of fresh watermelon and other snacks. At the second one, beautifully-woven fabric for skirts or sarongs was the main commodity - hardly surprising, since this whole area around Amarapura is an old-established center for the weaving industry. But Myint suggested instead that I do my shopping at the Scott’s market when we return to Yangon. Bagan (Pagan)

It was five in the afternoon, so I was quite tired and anxious to settle into my hotel. This was of course done with the usual dispatch and courtesy thanks to Myint and the driver. The Bagan Hotel was a delight. According to Myint, it is owned and designed by a Burmese architect from Mandalay. Like the Kandawgyi Palace, it incorporates local architectural and artistic features, with a brick front gate probably inspired by the 9th Century Sarabha Gateway which leads into the Old City. Everywhere in the grounds are earthenware pots with flowers in profusion, and vines running along fences, and lovely trees providing welcome shade from the relentless sun. The reception building is open and airy and remarkable cool, emanating a serene and welcoming charm with its simple wood furniture. My room was in one of the 10 separate low-rise buildings, each with its own service staff on the premises. The hotel grounds lead all the way down to the riverbank, and guests could be seen sipping their early evening cocktails on the lawn, while watching the sunset over the Ayeyarwady. The hotel’s literature speaks of “11th Century History with 20th Century Service.” And sure enough, we found two tiny 11th Century brick pagodas right on the lawn where we had our dinner al fresco. The flickering candle-light from the temples cast an evocative glow in its vicinity. Ancient Capital Bagan was the seat of the Burmese dynasty between the 11th and 13th centuries. The Kingdom of Bagan was founded by the Burmese as early as the 9th Century (847 A.D.), as testified by the Sarabha Gate on the eastern wall of the old city, the only intact structure dating back to the founding of Bagan. But it was not until 1044 when King Anawrahta ascended the throne that Bagan entered the period of frenzied building of temples and pagodas. After conquering Thaton in 1057, he effectively unified the country, and brought back to Bagan the Theravada Buddhist scriptures in Pali, thereby giving it a national religion. From Thaton he brought back Buddhist monks, artists, craftsmen and Mon architects. Thus began a period of exceptional flowering of religious, artistic and architectural creativity which was to last 200 years, and whose legacy of 2200 monuments in a small, semi-arid tract of land 16 miles long on the bank of the Ayeyarwady remains a Mecca for visitors from all over the world. During my 2-day stay here, I was taken to see somewhere between 10 to 12 monuments. I will only describe my impressions of some of these, which are considered to be either the most important or most representative. The

Shwezigon Pagoda

Ananda Temple Considered one of the most

fascinating and beautiful temples in Bagan, the Ananda was completed in 1091

by Kyanzittha, and said to be built according to a plan drafted by Indian

Buddhist monks. It

symbolizes the endless wisdom of the Buddha.

It is a whitewashed building shaped like a perfect Greek cross and

rising in progressively smaller terraces to a height of 170 feet, culminating

in a tapered spire and inverted umbrella or “hti.”

Standing guard at each corner of this venerable temple is an imposing

stone lion called “Chinthe,” which inspired the name “Chindits,” for

the almost legendary elite corps of British soldiers led by Orde Wingate who

secretly slipped behind Japanese lines during The War and weakened the

enemies’ communications and defenses sufficiently to lead to Japan’s

eventual defeat by Allied armies in Burma.

I had read about these soldiers’ ingenuity and valor long before

I came to Myanmar, so I asked Myint if she had heard of them.

She merely shook her head and said she knew nothing about them.

Just slightly north of the

temple is the Ananda Okkaung or monastery, whose walls are adorned with

beautiful frescoes which have retained a good deal of their vividness and

original colors. Some relate to

the life of Buddha, while others seem to be contemporary scenes of the court,

including intimate portrayals of the dissolute and luxurious life of the

nobility, in contrast to the Spartan existence of the slaves that serve them. Thatbinnyu Temple This temple was built during the 12th Century by King Alaungsithu. The word “Thatbinnyu” means omniscience, while “Ananda” comes from Ananta Panna, meaning boundless wisdom, both qualities of the Buddha which are symbolized by these temples. Located within the Old City, only a short distance from the Ananda, it was a pleasure for me to take pictures framing the whole of the Thatbinnyu from inside the Ananda, through one of the latter’s windows. At first sight, this white stucco building, standing tall and majestic, (in fact, at 200 ft., the tallest temple in Bagan) bears a strong resemblance to the Ananda, but it does not from a symmetrical cross. The “Pictorial Guide to Pagan” published by the Ministry of Culture gives a very visually-accurate description of the temple, “The high cubicles, the corner stupas on the terraces, the flamboyant arch-pediments and the plain pilasters combine to give a soaring effect to the monument.” Dhammayangyi Temple This one

emanates mystery and a raw power, even though it is unfinished.

A massive brick structure built in the early 12th Century by

King Narathu, who, having murdered his father Alaungsithu, wanted to make

merit through this construction project.

There are several theories as to why the temple was never finished.

One is that while the construction was in progress, a dispute over

trade in elephants arose between the Burmese and the Sinhalese, and the latter

attacked and conquered Bagan and had Narathu put to death.

Another explanation is that one of his queens, a Hindu princess, had

displeased him, so he had her executed.

In revenge, the princess’s father had him killed by assassins sent to

his court disguised as Brahmin priests. By

all accounts, Narathu seems to have been a nasty piece of work.

The Mon

Temples at Myinkaba A little south of the Old City

is the village of Myinkaba, where there is a cluster of Mon monuments,

including the three temples of Kubyaukgyi, Manuha and Nanpaya, characterized

by their square shape and dark corridors dimly-lit by sunlight streaming

through elegant perforated windows. The Kubyaukgyi was built in 1113 by Rajakumar, son of Kyanzittha. This typically Mon-style building has particularly finely-incised geometric designs for the perforated windows. In the interior, in the inner sanctum, are paintings considered to be contemporaneous with the temple and among the earliest now extant in Bagan. Of additional interest are the inscriptions in Old Mon under each of the scenes depicted. The Manuha Temple was built by

Manuha, the defeated and captive Mon king of Thaton in 1059.

Through the Temple, the king was making an eloquent and poignant

statement of protest about his own distressed and humiliated state and lack of

freedom by putting seated and reclining images of Buddha in tight, constricted

spaces. The Nanpaya is not far from

Manuha and was the king’s residence before it became a temple.

It is built of brick and mud and also has perforated stone windows,

though less intricate n design than the ones in the Kubyaukgyi Temple.

Inside are four stone pillars on each side of which are carved

triangular floral designs and figures of the Hindu god Brahma sitting on a

pedestal. I marveled at the fluid

lines of the carvings and the rich patina of their smooth surface, testifying

to the consummate artistry and craftsmanship of the sculptors. Sunset over

Bagan It was my last day in Bagan and

already late afternoon after a whole day of hectic temple-viewing.

Myint was anxious for me to see the sunset over this magical city.

She decided to hire a pony-trap to take me to Ywahaunggyi Temple where

the best view could be obtained. Before

long we were being driven by buggy through trails with jade-green acacias and

cactus on both sides, in the kind of profusion that I had not seen anywhere in

Bagan. It was a visually-pleasing

and exhilarating ride and I was sorry that it was over so soon.

When we arrived at the temple I found splendid cactus trees on the

temple grounds. I was led up to

the roof, which had no protective railings at all, so I watched my step.

A few tourists were scattered here and there, all armed with much more

sophisticated cameras than my point-and-shoot automatic Olympus.

Myint helped me find a space among a phalanx of German visitors who had

already staked out their positions and were poised for action with tripods and

zoom lenses. It was a delightfully tranquil summer’s evening. From the rooftop of the temple we had a commanding view of the plain in the foreground, and then the myriad of countless pagodas and temples, most of them dwarfed by the giants - Dhammayangyi, Ananda and Thatbinnyu. It was still clear and light, so we could still see the green trees alternating with expanses of yellow earth below us and also the soft whitish vegetation that looked like a kind of heather. In the far distance, beyond the pagodas and stupas, were the undulating blue hills that framed this picture.

Back to Yangon

Excursion

to Thanlyin ( Syrium ) My tour itinerary for my last

day in Myanmar was a day-trip to Thanlyin, about an hour’s drive from Yangon.

Our main destination was actually Ye Le Paya, or Pagoda in the Middle

of the Water, a short distance further south of the town of Thanlyin.

During the drive through the outskirts of Yangon, I noticed an

occasional government sign sternly exhorting Myanmar’s citizens to do the

right thing: “Obey the Law!” or “Do not align yourself with foreign

forces in a vain attempt to subvert our Government! “ It filled me with a

sense of foreboding that Big Brother was watching.

Apart from that, the landscape was rural and green, lush with paddy

fields, and all manner of trees and flowers.

I tried to learn and remember the names of the flora as best I could,

but without too much success. The Ye Le Paya was delightful.

We drove up to the jetty and boarded a small boat which took us to the

pagoda in the middle of the water. In

the mid-day sun, it was marvelous to feel the cool breezes from the river.

Once again, one could feel the rhythm and movement of pilgrims,

families and young people in groups, arriving and leaving, arriving and

leaving...in a never-ending process of worship and meditation. The shrine halls were filled with worshipers, among them an

immaculately-dressed old couple who Myint said was probably from the local

village. I leaned against the

railing and looked across the water at the houses on stilts in the village by

the riverside, framed by rows of dark-green palm trees behind.

All around the pagoda the narrow boats would churn up the brown water,

speeding backwards and forwards with their passengers holding bouquets of

flowers and other offerings, looking intent and purposeful.

The monks also availed themselves of this only form of transportation. It was a beautiful day, and there was a holiday atmosphere

here. Religion is serious

business in Myanmar, but there is also a side to it which is human, relaxed

and pleasant.

European house in Thanlyin

THE Food It had been a constant struggle

during my trip to persuade Myint that I really wanted to try Burmese food.

She, like many Burmese, thinks that foreigners do not enjoy their

cuisine, and invariably steered me toward Chinese food when meal time came

around. In fact, most Burmese

restaurants include a large number of Chinese dishes (of indifferent quality)

on their menus. How this

anomalous situation came about I do not know.

What Burmese food I did manage to sample was excellent.

Leaving

Myanmar My departure from Yangon went

without a hitch, and there were no last-minute unpleasant surprises at customs

and immigration. But then, I had

only picked up a few lacquer objects and lengths of woven silk and cotton

fabric to take home. No rubies or

sapphires, no important art objects. And

my Foreign Currency Declaration was not even looked at. As I waited for my flight to Bangkok at the departure lounge, I resolved to come back to this fascinating country. I had missed the fabled Inle Lake area in Shan state in the north-east. Rakhine state, near Bangladesh, has pristine, beautiful beaches and unsurpassed landscape and would be well worth a visit. It would be nice to see again Myint and Ko Ko Latt and everyone who had worked so hard to make my visit so memorable. People overseas choose not to visit Myanmar for reasons that could be personal or political. I also had some hesitation about going, but after all that I had seen and heard and experienced during this trip, I am irresistibly drawn to this land and its people, and I cannot see how I can stay away for long. |

I

was then driven to the dockside of Yangon, by the waterfront of the Yangon

River, where boats and steamers are moored and dock workers load and unload

sacks of rice or grain from barges that go up and down the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy).

I

was then driven to the dockside of Yangon, by the waterfront of the Yangon

River, where boats and steamers are moored and dock workers load and unload

sacks of rice or grain from barges that go up and down the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy).

In

1996, the local units of the Army painstakingly reproduced the original palace

buildings, with red buildings representing the lesser royalty at the western

end of the palace and gold buildings representing royalty of superior rank,

such as the king and queen, situated at the eastern end of the palace ground,

which was also where the main gate was.

In

1996, the local units of the Army painstakingly reproduced the original palace

buildings, with red buildings representing the lesser royalty at the western

end of the palace and gold buildings representing royalty of superior rank,

such as the king and queen, situated at the eastern end of the palace ground,

which was also where the main gate was. This

ornate building has finely carved wooden walls and intricate designs on its

panels and doors and lintels, on which traces of color and gilt can still be

seen - figures of dancers dressed in

This

ornate building has finely carved wooden walls and intricate designs on its

panels and doors and lintels, on which traces of color and gilt can still be

seen - figures of dancers dressed in The

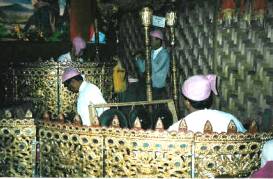

musical accompaniment to the puppet show was provided by the traditional

orchestra, the main instruments of which were the saing-waing and the kyi-waing.

The

musical accompaniment to the puppet show was provided by the traditional

orchestra, the main instruments of which were the saing-waing and the kyi-waing. I left the crowded cabin to get some fresh air on deck - it

was a peaceful and enchanting dawn.

I left the crowded cabin to get some fresh air on deck - it

was a peaceful and enchanting dawn. cloths

they had spread on the floor of the deck.

cloths

they had spread on the floor of the deck. After

a pleasant lunch on board and a brief siesta, we were getting closer to Bagan

already.

After

a pleasant lunch on board and a brief siesta, we were getting closer to Bagan

already. The

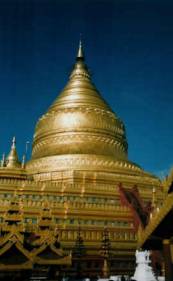

construction of this beautiful golden pagoda was started by king Anawrahta and

completed by King Kyanzittha in 1087.

The

construction of this beautiful golden pagoda was started by king Anawrahta and

completed by King Kyanzittha in 1087. The

exterior of this perfectly-proportioned temple exudes a quiet elegance - at

once understated and dignified (see left).

The

exterior of this perfectly-proportioned temple exudes a quiet elegance - at

once understated and dignified (see left).  The

overall plan has much in common with the Ananda, though the latter is more

elegant.

The

overall plan has much in common with the Ananda, though the latter is more

elegant. Before

long the evening light grew dimmer and dimmer until all of the foreground was

completely dark, and eventually only the unmistakable contours of the tallest

temples were starkly silhouetted against the brilliant orange-red sunset, with

the fiery sun still bright enough to irritate one’s eyes and hovering just

above the half-illuminated hills whose gentle distant outline was etched

against the sky.

Before

long the evening light grew dimmer and dimmer until all of the foreground was

completely dark, and eventually only the unmistakable contours of the tallest

temples were starkly silhouetted against the brilliant orange-red sunset, with

the fiery sun still bright enough to irritate one’s eyes and hovering just

above the half-illuminated hills whose gentle distant outline was etched

against the sky. After

leaving Bagan, I was given an extra day and a half in Yangon.

After

leaving Bagan, I was given an extra day and a half in Yangon. I

had read that Thanlyin had been a Portuguese trading post during the 17th

Century, when a Portuguese community began to settle there.

I

had read that Thanlyin had been a Portuguese trading post during the 17th

Century, when a Portuguese community began to settle there. At

the fabulous Riverside Restaurant in Bagan (see left) I had a delicious prawn

curry - it was not all that spicy, but very flavorful, served with an endless

supply of piping hot rice (can’t imagine there would be a shortage of that

commodity in Myanmar!).

At

the fabulous Riverside Restaurant in Bagan (see left) I had a delicious prawn

curry - it was not all that spicy, but very flavorful, served with an endless

supply of piping hot rice (can’t imagine there would be a shortage of that

commodity in Myanmar!).